Wagnerism in the Shadow of Black Lives Matter

Alex Ross's Testimonial to the Life, Times and Art of Richard Wagner

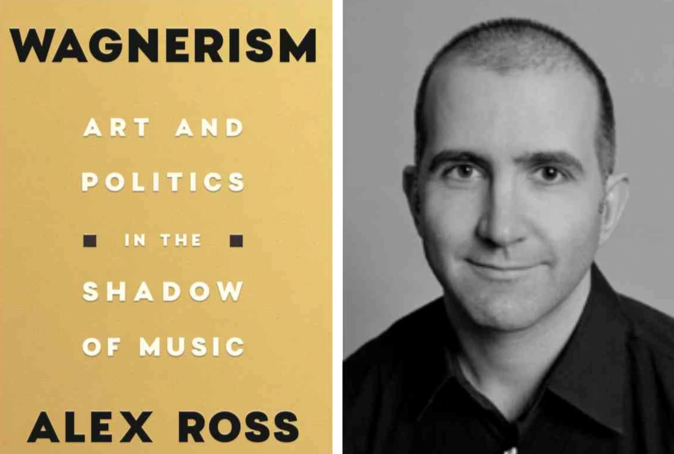

Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music by Alex Ross

For every window on Wagner we think we've already peered through, Ross has found more lenses and prisms through which to re-view them. At his best, Ross gives dimension to individuals, artworks and events, and captures their intersections with one another and the wider world of the past. But for all its evocation of the life and times of Wagner and the "artwork of the future" — Wagner's and that of his many disciples, there's little that looks to a salutary future for Wagnerism.

Alex Ross's Wagnerism is erudite, expansive and elegiac. Extensively annotated, compellingly laid out and compulsively readable, it's brimming with juxtapositions and gems of detail and insight. Its greatest success is in demonstrating with endless examples what we already know — how widespread and powerful Wagner's appeal has been to so many individuals and factions of culture, politics, history, religion, race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality.

As everyone also knows, Wagner's art is dogged by questions of its entanglement with the character and prejudices of Wagner the man and his place in the advent of Hitler and Nazism. However otherwise gifted and influential as an artist, the documentation and affirmation of which are the principal motivation and achievement of Wagnerism, Wagner was also a colossus of grandiloquence and mean spiritedness. Legendarily bigoted, spiteful, vindictive and heinously antisemitic, he was redolent of Donald Trump in being mendacious, appropriating, and a divisive, sadistic, bullying, tyrannizing, predatory, scapegoating German and white supremacist. Whatever else he was, he was also, to quote Alex Ross — in turn quoting Auden, who also called Wagner "perhaps the greatest genius who ever lived" — "an absolute shit."

In view of the virtually universal recognition of Wagner's greatness as a composer even among his detractors, it comes as no surprise that Ross, whose own Wagnerism is hardly a secret, is easily successful in re-establishing Wagner's art as the most protean, in terms of its allure and impact, in the history of musical culture. At the same time Ross is skilled at demonstrating the balance of complex forces at work in Wagner's imprint on individual lives, times and, with infectious enthusiasm, his milieus. Though the book is close to 800 pages, Ross retains his gift for rendering complexity with acuity and economy.

Ross is adroit, for example, in sketching in a few sentences how Tannhäuser's journey could be so viscerally appealing to Theodore Herzl, the founder and visionary of Zionism, and as well to W.E.B. Du Bois in his pursuit of a heroic new African spirit. He's comparably adept in parsing how, beyond questions of antisemitism and homophobia, an exemplar of self-hatred like Otto Weininger could engage so much interest. The relationship between Wagner and Nietzsche seems more accessible here than when we kept trying to put the pieces together ourselves.

Setting the stage by opening with the closing event, the composer's death in Venice in 1883, Wagnerism commences with "Rheingold," a look-back reminiscent of the Hollywood heyday movies Ross later explores as having been so inspirited by Wagner. A whirlwind tour of Wagner's creative life ensues with the Ring cycle components as touchstones and in counterpoint to Wagner's vacillating relationship with Nietzsche.

Along the way of what's only the first 64 pages, we are helped to gauge Wagner's artistic maturation within the Ring itself and in the two great operas, Tristan and Meistersinger, that were composed amidst the mammoth 26 year project of the cycle. Onward to the events leading to the establishment of the Bayreuth Festival in 1876 and the groundwork for Parsifal and its early controversies.

A later chapter, "Grail Temple," begins with a survey of the "Esoteric, Decadent and Satanic Wagner" that encircles the Wagner of Parsifal that Nietzsche found so objectionable. Past pages on the philosophical murk of so much Parsifal literature, art and commentary, however, we still don't have the summary perspective of key issues and controversies Ross can be so good at. That may be more because of Wagner's cunning than Ross's inadequacy. As Wolfgang Wagner put it in a backstage aside in Tony Palmer's film of and about the opera, does anyone really understand Parsifal?

Meanwhile, however, neither he nor Ross wants to underscore that in its portrait of Kundry, however otherwise enigmatic and compelling her character and notwithstanding such phenomena of Jewish Wagnerism as Thomaschefsky's Yiddish rendering of the opera in Brooklyn in 1904, Parsifal showcases and perpetrates the most incendiary of antisemitic slanders: that of the Wandering Jew who laughed at Christ's Crucifixion agony. Because of its stature as supreme composer Richard Wagner's last and most musically advanced work, and because of obligatory reverence for it by multiple parameters as Heilige Kunst, and notwithstanding references to the Wandering Jew in other artworks and literatures, Parsfial becomes the most potent and portentous weapon of antisemitic propaganda in the history of art.

Stripped of its high art trappings, what Wagner does to the Jews in Parsifal is what Trump and QAnon have done to Hillary Clinton and the Democrats, without the "compassion" but with comparable malevolence.

Antisemitism is present in the work of many composers, from Bach to John Adams (Kissinger in Nixon in China is as much an antisemitic caricature as Beckmesser in Meistersinger, neither of them specifically designated by their composers as Jews), but in its depictions of the black arts seduction evils of Kundry and her self-castratingly envious master, Klingsor, the antisemitism of Parsifal is truly in a league of its own. It's right up there with, and firmly in medieval German Volk traditions of, rendering Jews as witches and Satanic demons with horns, hooves, tails and forked tongues.

In his review of the Met's revival of Parsifal for his New Yorker column, Ross seemed deeply moved by director Francois Girard's compassionate portrayal of Kundry — so compassionate that she doesn't clearly die at the end as she's directed to do by Wagner. And it's she in this production, rather than Parsifal, who raises the Grail cup as the opera concludes. Just as Wagner, having done the damage of laying out the libel against her, against the Jews, is then inclined towards crocodile-tears forgiveness, so is Ross inclined towards what are ostensibly the opera's transcendent themes of compassion and forgiveness. As Wagner apologists are wont to do, Wagner's more humanistic meanings and intentions are intuited and projected onto the opera as well as the composer. Even if they are genuinely there, however, the old libel of Jews as mockers of Christ, like the Passover blood libel, is preserved and consecrated as never before and nowhere else in the highest ranks of art.

Somehow mitigating the odium of the Wandering Jew for Wagnerites is its presence as a theme throughout Wagner's own life and work, going back to his first major operatic success, The Flying Dutchman, based on a tale by Jewish Heinrich Heine. Confounding as well, it can seem, is the character of Wotan as the Wanderer in Siegfried. Here, Wagner's stand-in has become so diminished in his dealings with the Nibelungs — the Jews — and the resulting devolution of all that he has virtually become a Wandering Jew himself.

And the source of Wagner's venomous preoccupation with the Jews? Here, as in other passages in Wagnerism, Ross shows his gift for staring Wagner's antisemitism in the face and saying what needs to be said, albeit with Ross somehow emerging from these skirmishes with his Wagnerism undiminished:

"Political sentiments and professional jealousies fail to explain the fervency of Wagner's hatred...It welled up from deep in his psyche. As he admitted to Liszt: 'This rancor is as necessary to my nature as gall is to the blood.'"

Stripped of its high art trappings, what Wagner does to the Jews in Parsifal is what Trump and QAnon have done to Hillary Clinton and the Democrats, with greater "compassion" but comparable malevolence.

In the throes of antisemitic obsession, Wagner can be seen in another paradigm of human behavior, one also touched on by Ross— that of intoxication, compulsivity and addiction. More on that anon.

The story of Nietzsche pro and contra Wagner is deftly interwoven throughout Ross's narrative. For what may have seemed a more clear-cut break around polarities between the two figures, Ross notes of the outcome that "Wagner and Nietzsche darkly complete each other in the Nazi mind," though it's Nietzsche who gets the last word in Wagnerism: "One day my name will be linked to something monstrous — to a crisis like none there has ever been on earth." To a monstrous crisis, yes, and to the monstre sacré, Wagner, who enkindled it.

Reflecting our own attraction and ambivalence, Nietzsche is an ideal companion to accompany us on Ross's junket. Inspired by the Patrice Chéreau centennial production of the Ring at Bayreuth, Ross writes of the conclusion of this towering creative achievement that the Wagner-Nietzsche relationship nurtured: "the most monumental artwork of the nineteenth century is merely a prelude to future creation. The audience must write the rest."

The book then moves into a narrative of Wagnerism as it bewitched, invaded, wrought havoc and flourished in various milieus — French, British, German, Jewish, Feminist, Black, Gay, Lesbian, American, Russian, Marxist, Socialist, Boleshevik, Nazi, Modernist, Poetic, Occult, Symbolist, Theosophist, Psychoanalytic, Futurist, Dadaist, Fabian, Romantic, Weimarian and other stopovers on its Wanderer's road to where it has ended up — Hollywood. Much of this material, updated for this collection, appeared over the years in Ross's New Yorker column.

Ross inventories a wide range of notable artworks in relation to Wagnerism. From the novels of Charles Dickens and George Eliot to those of Garbiele D'Annunzio, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Hermann Hesse, Franz Werfel, Robert Musil, Joseph Conrad, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Marcel Proust and Upton Sinclair to the poems of Sidney Lanier and T.S. Eliot; from the danse moderne of Isadora Duncan to the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghalev; from the drawings and paintings of virtually all of the leading French Impressionists and post-Impressionists to expressionist Wassily Kandinsky and mixed-materials German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer; from the skyscrapers of Louis B. Sullivan to the fantastical edifices of Antoni Gaudi. In many instances, works, especially novels, plays and poems such as those of Joyce, Woolf and Eliot, are summarized and interpreted from standpoints of Wagnerism. The panorama can be breathtaking. In the encyclopedic inclusiveness of its many inventories, which as such can eventually seem formulaic, it can also be stultifying.

The first major stop on the Grand Tour of Wagnerism, "The Tristan Chord," recreates Wagner's experience in Paris and with the French. As most everywhere else, Wagner's impact was momentous, inspiring individuals, artworks, movements, tracts and upheaval. Yet for all the stars in the French firmament of Wagnerisme, the French cult of Wagner— Baudelaire, Mallarme, Verlaine, Cezanne, Gaugin, Von Gogh, Renoir, Monet, Delacroix, Zola, Gautier, Sand, Maeterlinck, Proust, Bizet, Saint-Saëns,— what struck me was Ross's observation that "[Wagner's] reputation depended in large measure on his revolutionary pamphlets" (with their miasma of revolutionary antisemitism) and his conjoined observation that Wagner "had many fans on the left."

Tony Kushner's effusive blurb for Wagnerism reads like a capstone to this enduring reality. Ross quotes Wagner's contention that "only when the demon [money] that keeps people raging in the madness of party conflict can no longer find a time and place among us will there be — no more Jews." In this are the similarities between Wagner and Karl Marx in the latter's tract,"On the Jewish Question," that can so resonate with partisans of the Left, not a few of them Jewish.

Likewise arresting from that period and milieu of the French is another clue to his art from Wagner himself: "The mark of a great poet is to let the public grasp in silence what is left unsaid." As Ross later observes, the absence of characters specifically designated as Jews in Wagner "enabled liberal Wagnerites to create a kind of firewall between the composer's despicable views and the ostensibly humane content of his works."

While Ross can be unflinching in denoting antisemitism, widespread in France as elsewhere in Europe and beyond, that attributed to Degas and Renoir is not explored in context. There's mention of Degas's hooked-nose Jew at the Bourse, and Renoir's portrait of a fleshy Wagner is one of Wagnerism's sparsely identified illustrations, many of them so small and grainy in black-and-white you have to squint for clarity. Mention also should be made of Wagnerism's flat chartreuse-yellow cover with no design. Certainly, there will be enough readership for this important book, whatever the caveats, to justify better presentations of it.

Early in his chapter, "Swan Night," on Victorian Britain and Gilded Age America, Ross quotes at length from an otherwise unremarkable entry in the Nebraska State Journal in 1894 on a wedding that took place in Lincoln to the organ accompaniment of "the triumphant tenderness of Wagner" (The Bridal Chamber music — "Here Comes The Bride" — from Lohengrin). Its author was "a precocious University of Nebraska student named Willa Cather."

There's no discussion at this juncture of what some have imputed to be Cather's antisemitism, racism and views that could be considered reactionary, which Ross does touch on later in an extended consideration of Cather, her work and background ("Brunhilde's Rock: Willa Cather and the Singer Novel," is an entire chapter devoted to her).

In being more open to exploration of racism and antisemitism in American Wagnerism and elsewhere, Ross at first can seem in contrast to Joseph Horowitz, whose history of Wagnerism in turn-of-the-century America, Wagner Nights, Ross acknowledges as authoritative. For Wagner apologists, however, Wagnerism will cinch Horowitz's implicit case that Wagnerism in America at the turn of the century had little or nothing to do with racism and antisemitism. As with Horowitz, this transcendence of Wagnerism beyond the confines of still incendiary issues of race and antisemitism is the thrust, heart and soul of what Ross most wants to tell us about Wagnerism's place in our lives and times, past and present.

Subsequent chapters delineate manifold phenomena of Wagnerism. The pre-Raphaelites and art-nouveau decadents were mesmerized, Ross observes and as we know from the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley and others, by the eroticism of the Venusberg and Tristan. But "most of all, Wagner captured the Victorian imagination because of his proximity to the Master of Britain — the tales of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail."

Of keen interest is the material on British novelist George Eliot, a musician herself and admirer and social consort of Wagner, as possibly the first to use the phrase, "the propaganda of Wagnerism" in her unsigned 1855 essay, "Liszt, Wagner and Weimar." Despite her later essay on "The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!," evincing alarm about the escalation of antisemitism, and notwithstanding the expositions on Jewishness of her "proto-Zionist" novel, Daniel Deronda (published in 1876, the year of the Ring cycle premiere), Ross notes that Eliot may not have seen Wagner's essay "Jewishness in Music," likewise unsigned at that time (in its initial printing of 1850), and may not have appreciated the extent of Wagner's own antisemitism.

Fast forward to the concluding chapter on Hollywood, which unfolds feverishly and is so top-heavy with names and references as to seem more a catalogue or appendix than a denouement. At first it seems ironic, even funny and a kind of justice that Wagner should end up being so appropriated by Hollywood, with its predominance of Jewish refugee and emigre composers, film producers, directors and actors. But bemusement fades as one realizes that what Ross is leading up to is his sense that Hollywood's exploitation of Wagner for its blockbuster films is not only a kind of propaganda, as America descends ever further into racism and fascism, but as well a playing out of Wagner's vision. As Ross concludes in his adaptation of this material for his recent New Yorker piece, "Wagner in Hollywood":

"The urge to sacralize culture, to transform secular pursuits into secular religion and redemptive politics, did not die out with the degeneration of Wagnerian Romanticism into Nazi kitsch."

What can be gleaned between the lines here is the Shavian, socialist view of Wagner that Ross looks at in other contexts and that was the basis of that legendary Bayreuth Festival Centennial Ring cycle production. Staged as a parable of the Industrial Revolution and modeled on The Perfect Wagnerite of George Bernard Shaw, Chéreau's Nibelungs were overtly depicted as Jews. Connecting the dots, what Ross is insinuating, however paraconsciously and elliptically, is that the answer to questions of the future and its dangers, to the question asked by Friedelind Wagner in her introductory comments to the telecast of the Chéreau Ring — "Who knows when another Alberich will come along to set the entire cycle in motion again?" — may be glimpsed in Hollywood and the hegemonics it increasingly betrays.

"It would be a mistake to say that Shaw and his fellow leftists found the 'true' Wagner," Ross concludes in his chapter, 'Ring of Power: Russia and Revolution.' "But it would be a mistake to say they misunderstood him."

For all of Wagnerism's evocation of the life and times of the "Sorcerer of Bayreuth," an appellation attributed to Nietzsche, and of Wagner's "artwork of the future," however, and even with its malleability within infinite avenues of political interpretation, a more certain and salutary direction for Wagnerism in the future is neither conceptualized nor invoked by Ross.

The socialist perspective of Wagner showcased by Chéreau is inescapably betrayed by its double vision. On the one hand Jews are seen as victims of racism and antisemitism. On the other they are indicted for being premiere perpetrators of the capitalist greed that leads to their own undoing and that of everyone and everything else. In its double-think it can echo the double talk of Donald Trump, today's supreme practitioner of hypocritical blame-the-victim stratagems and oratory. Trump rages against "socialism" as he plots and schemes in collusion with leading socialist autocrat Vladimir Putin for police state dictatorship power, just as Wagner raged against the very materialism he himself coveted, demanded and wallowed in. In both cases, left and right elide via their common ground of authoritarianism, racism, antisemitism and scapegoating. Antisemitism — "The Socialism of Fools," Seymour Martin Lipset called it, echoing the German Social Democrats of the Wagner era, in his blistering critique of antisemitism on the Left in the New York Times in 1971.

Concluding his section "Wagner in America," Ross observes that with polarities of viewpoint on gender and race predominant, "Wagner's work and ideas provided fodder for both sides of a battle over American identity that is ongoing."

In "American Siegfrieds" Ross looks at the contributions of poet and musician Sidney Lanier and his ode to Wagner. His assessment of the limits of Lanier's efforts to try to develop a narrative to tell the stories of Native Americans (The Song of Hiawatha) is perspicacious:

"The idea of a national mythology based on the legacies of conquered, murdered and enslaved peoples was not one for which Wagner provided a precedent."

Though Ross notes upfront in Wagnerism that Lanier, the most famous son of my hometown of Macon, Georgia, fought for the Confederacy, it's not denoted in context that some institutions named after him have since changed their names because of that legacy. Ross does not designate any overlap of Wagnerism and racism in Lanier, as he does with Lanier's contemporary, Owen Wister, likewise a poet, author and composer. Wister is best known for The Virginian, a cowboy novel that was the basis of Hollywood films.

As Ross has written elsewhere and as is otherwise well-established, American racism was extreme and variously conjoined with antisemitism (e.g., Henry Ford). It had many manifestations beyond slavery, many theorists and leading practitioners, and was antecedent and contributory to Nazism. Yet, any linking of that reality to its presence in Wagnerism in America can draw reflexive blanks from those inclined to Wagner apologism. In Ross's narrative, as in Joseph Horowitz's Wagner Nights, one can sense that firewall for liberals Ross described between the composer's despicable views and his ostensibly more benevolent influence.

To what extent does the audience appreciate that it is being invited to legitimately participate, albeit tacitly and under the mantle of high art, in levels of racism and antisemitism that are otherwise proscribed?

In Parsifal, Gurnemanz explains to the young knight that in the realm of the Grail, time and space become one. In the real world, or rather in escaping from it, there's another place where time and space meld. That place is one I've come to recognize from my personal background and work in addiction, and from my own experience of Wagnerism. It's the realm of what Gottfried Wagner calls "Wagner intoxication." As it progressed (in the vocabulary of addiction "progression" is used to denote the advance from intoxication to addiction) in my own life and milieu, and thoughit's something more intuited than scientifically quantifiable,Wagnerismcan seem fueled by this process; as can Ross and his book.

That Wagnerism can exude the exhilaration and intemperance of drug addiction is not a new idea; nor that Wagnerism can be cultish, a descriptive Ross himself isn't shy about using. Notwithstanding that they don't discriminate on the basis of identity, both phenomena — addiction and cultism — are notable for their insularity. This phraseology of Wagnerism in metaphors of drugs, intoxication and addiction, like those of sorcery and enchantment, is familiar to Wagnerites.

"Lisztomania" is a term coined by Heinrich Heine, the Jewish writer Wagner admired and whose original tale of The Flying Dutchman Wagner reconfigured for his own opera, to denote the frenzy of fandom surrounding Franz Liszt, the composer who would become Wagner's father-in-law. Wagnerism can seem similar in suggesting intensities of feelings that can be irrational, transitory and more in the nature of altered states of consciousness. While it might appear open-minded and inclusive, the cult of Wagnerism, like other cults (e.g., Trumpism) can be notably intolerant of dissent and disloyalty. However sober in narrative and however of value and interest its history, Ross's exhaustive compendium is testimonial to Wagnerism, rendering Wagnerism itself exemplary of the cultism it so extensively documents.

Wagnerism, which Ross makes little effort to define — yes, it's that vast, we intuitively concede — is something you can sense the first time you notice the enraptured, absolute quiet of a Wagner audience or the outsizedness of Wagner ovations, even for mediocre performances. Mainstream opera enthusiasm can become rowdy with cheers and boos, but the thunderous force of a Wagner ovation can seem of another species. In contrast to the standard repertoire works that showcase singers, Wagner himself is more discernibly the font of this most passionate enthusiasm of operatic experience.

Past the peak of progression of my own Wagnerism, this roar of Wagnerian ovation began to resound with greater menace. It seemed less secure, less the Heimat it had seemed to me in the throes of Wagnerism oblivion and denial. As I became evermore lost in the perfumed gardens of Klingsor and Kundry, I began to realize with gathering discomfort that I no longer felt I knew what that roar of the crowd was really all about. Was it truly, solely and simply in response to Wagner's musical and theatrical genius?

Further along in my own process of self-detoxification from Wagner, I realized I will never again be able to experience that roar as divorced from the darker energies wafting within and about Wagner and Wagnerism. The question that always lurked there had finally broken through: To what extent does the audience appreciate that it is being invited to legitimately participate, albeit tacitly under the mantle of high art, in levels of racism and antisemitism that are otherwise proscribed?

In his section, "Democratic Vistas," Ross looks at Mark Twain, a cockeyed Wagnerite who wrote of his 10-day trek to Bayreuth, and of his experience of Wagnerism:

"Sometimes I feel like the one sane person in a community of the mad; Sometimes I feel like the one blind man where others see; the one groping savage in the college of the learned; and always, during service, I feel like a heretic in heaven."

If you knew nothing else about this passage, you might be persuaded that it's the description of a first visit to an opium den.

Rounding up his survey of Wagnerism in America, Ross looks at America's greatest poet. It has always been a bit of a mystery that opera-loving Walt Whitman, whose heyday overlapped with the early Wagnerism movement in America, had little to say about Wagner, a casualty more of timing, Ross deduces, than of taste. To this Ross adds the resonant perspective that for some, Whitman's free verse and freethinking were the counterpart of Wagner's art of the future.

Though notable for its many windows and prisms, Ross's surveying of Wagnerism in America, with its formidable inventory of Wagnerism in Hollywood films and including many snapshots of gay, lesbian and Jewish Wagnerism, has important omissions. One of the bigger and more baffling of these, since it so impressively makes Ross's case for Wagner's impact on gay and Jewish sensibility and creativity, is The Twilight of the Golds, the play by Jonathan Tolins about Wagner, Jews, gayness, genetics and the future that ran on Broadway and was subsequently made into an award-winning film.

In his ambition to capture every nuance of the history and experience of Wagnerism Ross may not be scrupulously comprehensive, but he mostly seems bold, clear-eyed and comprehensive rather than intoxicated or evasive. Yet, for all its intelligence and careful covering of bases, key issues can feel sketchily explored, and the insularity of Wagnerism can seem to keep intruding, like the chalky faces in the offbeat film of encroaching death, Carnival of Souls. While the overarching specter of racism is touched on by Ross in multiple particulars and from different vantage points, including those of black artists, the result can be a slipperyness of perspective of Wagner's place in what eventuated in Germany, engulfing the wider world.

Luranah Aldridge was a mixed-race American soprano who was enlisted by the Wagners to sing one of the Valkyries in the world premiere of the Ring cycle at Bayreuth. Instead of placing her in a clearer context of racism in Wagner, in America and for Germany, which Ross does evoke elsewhere — e.g., in relation to Du Bois and his visit to Bayreuth in Ross's discussion of "Black Wagner" — we're presented with confounding glimpses of the Wagners' graciousness and friendliness to Aldridge against the grain of what we know to be their Weltanschauung regarding race.

As with Angelo Neumann, Wagner's Jewish international agent, and even with the more challenging case of Wagner's Parsifal conductor, observantly Jewish household guest and Wagner pallbearer Hermann Levi, the son of a rabbi, when it came to their own ambitions, the Wagners' principles could be relegated and prejudices muted. It's left to us to decide if these exceptions to the rule mitigate stereotypes of the Wagners around race and antisemitism to the extent that they seem to have done for Ross. Alternatively, perhaps what Ross is trying to elucidate is that while Wagner was clearly and profoundly antisemitic, the racism with which his antisemitism was entangled was notably less extreme and personally invested.

Ross's takes on racism and antisemitism can otherwise seem like generic white liberal takes on these matters. While such efforts to make things right and put them in perspective appear laudable in motivation and presentation, we have that sense of something missing. In the case of racism, what the usual cast of today's white liberal spokespersons has to say may be insightful and caring, but as Black Lives Matter is helping us better appreciate, what has been missing are the multitudinous, previously ignored voices of everyday black experience and sensibility. Their stories — especially of the likes of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and many others who have been so notably victimized— are finally being told and heard as never before.

Just as gay people of my generation grew tired of hearing ourselves described by heterosexuals and tired of seeing ourselves portrayed onstage and onscreen by heterosexuals, just as women have grown tired of hearing themselves spoken for by men, just as Hispanics and Asians have grown tired of seeing and hearing themselves portrayed and characterized by Caucasians, and just as blacks have reached their limits in terms of having their lives accounted for by whites, I can't be the only Jew to have grown weary of having my reactions to Wagner paraphrased and spoken for but otherwise ignored by others, notwithstanding their learning, ostensible compassion and good intentions.

Beyond the notable achievements of Wagnerism, distinguished by intellectual dexterity, a literary gift for engaging readers and a careful willingness to articulate how serious and odious Wagner's antisemitism can be, a question lingers, the very question that Ross cites as lingering at the conclusion of the Ring cycle. Where do we go from here?

I don't think anyone has the answer to that. But why not look for it, even in what might seem unlikely or suspect places? Not so exclusively in the art, memoirs and artifacts of the famous, infamous and offbeat that are the more predictable bedrock of scholarship as in Wagnerism, nor even at the historical and political developments that have so exhaustively inspired deconstructive postmodern stagings and cinematic appropriations of Wagner, but from the more mundane worlds of music and opera surrounding us.

Just as Black Lives Matter challenges even the most liberal and tolerant among us to see a greater landscape of black life and experience, so the ongoing scholarly ferment in Wagner circles around antisemitism should be more open to a greater canvassing of Jewish experience with a more forefront participation by self-identified Jews in that discourse. For all the discussion of Jews, antisemitism, Wagner and Wagnerism by Ross and many others among the dramatis personae in Wagnerism, however, such testimony per se is rarely if ever solicited or demarcated as such. Nor is its absence noted.

Testimony like that of my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite remains all too foreign in these realms — rare, suspect, unwelcome and ignored. It makes me feel like Twain at Bayreuth or that civilian in the opium den. In any context, of course, if you're a wheel but not willing to be squeaky, you're not likely to get oiled.

Not so unlike the slaves who voluntarily stayed with and fought for their Southern masters during the Civil War in Gone With The Wind, Jewish Wagnerites can seem generically and notably out of touch with our feelings about antisemitism and as well our ethnicity. As William M. Hoffman (Ghosts of Versailles) has put it, the post-Holocaust generation of Jews is numb.

Those of us who are liberal and urbane almost uniformly, wishfully think of ourselves as culturally cosmopolitan and well assimilated in our Wagnerism, the very hiding places Wagner, with Nazism in hot pursuit, so ruthlessly, relentlessly, obsessively and sadistically routed and indicted in his artworks, essays and other writings.

In Wagner's time and yet again in our own, we Jews have been all too susceptible to internalizing this prejudice, to introjecting mainstream viewpoints and judgments. Where conflict is recognized it tends to be denied, universalized, relegated, rationalized and dichotomized (bad man/great art). Not much more than in Wagner's time, and most paradigmatically in the case of Wagner himself, have the keepers of the flame of Western culture had much interest in or tolerance for "whiney" Jews, any more than for "uppity" blacks, or for "shrill" white or "angry" black women.

While it's now evermore widely accepted that Die Meistersinger and its caricature villain Beckmesser, along with other of Wagner's characters and situations, are infused with Wagner's antisemitism, few Wagnerites will admit that these stereotypes have or ever did have much currency in the mainstreams of Wagner appreciation. The most skillful of Wagner's defenders, like Ross, now acknowledge the composer's antisemitism warts and all, but still emphasize the ambiguities and absence of antisemitic specificity in the works themselves.

Pause for a moment to recall Ross's quoting of Wagner on the importance of not spelling everything out. Juxtaposition of that with Wagner's palpable rage over "mimetic" Jewish efforts to assimilate in their lives and art exposes a bigger picture of the ongoing dangers of Wagner's antisemitism. It's in this sense that my observation can reverberate:

Those of us [Jews] who are liberal and urbane almost uniformly, wishfully think of ourselves as culturally cosmopolitan and well assimilated in our Wagnerism, the very hiding places Wagner, with Nazism in hot pursuit, so ruthlessly, relentlessly, obsessively and sadistically routed and indicted in his artworks, essays and other writings.

Among the most articulate and influential of these spokespersons of Wagner's nonspecificity is Hans Rudolf Vaget, whose guidance is generously acknowledged by Ross in Wagnerism. Though they would bristle at being so labeled, a beneath-the-surface defensiveness of both Ross and Vaget can invite us to see them in a wider context of the Wagner apologism that few admit to but which seems key to the sustenance of Wagnerism.

Like Vaget, Ross is often at pains to establish the complexity of what might seem more monolithic considerations. "Once we get away from the concept of...some sort of supernatural master-disciple relationship," Ross notes in paraphrasing Vaget, "we can form a balanced, if still unsettling, picture of the Wagner-Hitler problem."

Actually, it's Vaget's contention, quoted by Ross and bolstered by Wagner's statements on the importance of taciturnity as opposed to literality in art, that "Wagner aspired to broad, even universal acceptance and therefore took pains to keep any overt indication of his very particular anti-Jewish obsession out of his operatic work."

The problem with Wagner apologism, a term that can be used accusatorily and that isn't explored in Wagnerism, is not that it seeks to exonerate Wagner but that it can betray its own ostensible openness to interpretations of Wagner. When Ross later dismisses Nazi readings of Wagner for their superficiality, romanticization and gutting of Wagner's complexity, it can seem tacit that he's also apologizing for Wagnerism's most shameful and tragic depths and mistakes.

I'm reminded how I myself, with secret shame for my Jewishness when I was growing up in Macon, Georgia in the l950's, might say things like, Yes, I'm Jewish, BUT I'm not religious. Yes, there are troubling issues in Wagner BUT...Yes, some Nazis apparently played Wagner in the camps, BUT, Ross notes, few camp survivors attest to much presence of Wagner's music during their internment. Beyond this endless balancing act, and when all is said and done, that Nazis read what they did into Wagner seems no more or less legitimate than the ways in which many other Wagnerite factions have interpreted and appropriated the composer. The Wagnerism of Hitler and Nazism, in other words and it bears repeating, was no less legitimate or more unreasonable a reading of what's actually or intuitively there in Wagner than any other avenue of interpretation.

Antisemitism, racism, nationalism — all of these were major strains in Wagner, emphasized by some and relegated by others. In its varied, fragmentary, prismatic, qualified and irresolute assessments of the interrelationships of Hitler, Nazism and Wagnerism, "Yes, BUT..." is in fact a leitmotif of Wagnerism. But in this Ross is hardly alone. In fact, he's in good company. The Wagnerite Ross stands in greatest admiration of — Thomas Mann — was comparably conflicted and found himself variously in stances of affirmation, condemnation, defensiveness and apologism. Despite pages on Mann and his magnum opus, Dr. Faustus, however, clarity on Wagner remains elusive for Ross. Mann never had it. Nor does Wagnerism.

Most observers, including Ross, now concede that the stratagem of emphasizing Wagner's nonspecifity fails with Die Meistersinger, where Vaget can remain on defense. Closer to home, we Jews are inevitably troubled in our relationship with Wagner and do betray a bumbling Beckmesserian insecurity about our place in reaction and relation to Wagner. In our embrace of Wagnerism, we seem all too often like black Republicans in relation to Trump, too easily in betrayal of some of our deepest sensitivities and self-respect. Like Alberich and Mime, we're more likely to be at odds with each other than to confront the prejudices of greater nemeses.

To find a Jew who recognizes and articulates how much conflict can be involved in Wagner appreciation, who is not psychopathologically in denial and is willing to express themselves about this and find even a marginal platform for doing so remains rare. So rare, in fact, that I remain a singular example.

Yes, of course, there have been admissions of conflict and discomfort from Jews historically and today. There were even Jewish protests during Wagner's time, as noted in Wagnerism, though not in our own time, as not noted in Wagnerism. But as with blacks in pre-BLM America, testimony of the depth and extent of this turmoil has remained subservient to broader perspectives and platforms of accommodation and inclusion.

Jews are and always have been a conspicuous coterie of Wagnerism and Ross does marvel at the varieties of Jewish experience in these realms— e.g., Mahler, Schnitzler, Adorno, Hanslick, the refugee emigres to Hollywood and many others, and as well in various milieus such as in Israel, and in France, where the term Wagnerism (Wagnerisme) appears to have originated.

There's the legendary Tomaschevsky Brooklyn Yiddish Theater Parsifal in the lineage of conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. There's Karl Tausig, the Polish-Jewish pianist who became Wagner's disciple and friend. There's Wagner's romance with part-Jewish Judith Gautier. There's gay and Jewish Weininger, whose life, work and suicide Ross explores with fresh detail and perspective. There's Levi, who Ross sees as more independent than codependent. There's "Wagner's Jew" Josef Rubenstein, and Angelo Neumann. There's likewise commentary on Schnitzler's book The Road [or Path] Into The Open, about Jews and antisemitism in fin-de-siecle Vienna, this time referencing the pioneering work of Germanist Marc Weiner, who has notably engaged with Ross's mentor Vaget in debates about Wagner's antisemitism at Harvard and in the German Quarterly.

In the richness of its explorations of Wagner's antisemitism and that which was ambient in Wagner's time and milieu, Weiner's Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination is a benchmark and bellwether of Wagner studies. (See my commentary on Weiner, "Pandemic Wagnerology," on medium.com). Notwithstanding Weiner's own Wagnerism, however, his membership in the Wagnerism Club is still in dispute. Beyond referential acknowledgment, his work is not sentient in Wagnerism or otherwise among Wagnerites.

Returning to the challenge of making the case for a greater probing of the conflictedness of Jewish Wagnerites, let me recount my own moment of direct experience with Ross. What follows is excerpted from "Pandemic Wagnerology":

"Nor, for that matter and not surprisingly, has [Ross] mentioned my work. I know he has seen my Confessions because I personally handed him a copy following a talk he did on "The Wagner Vortex" in 2012. When I gave him the book he recoiled, saying he'd already seen it, thank you. But it's inscribed to you, I persisted. As I have with other Wagnerites not known to be Jewish, I inscribed it as follows: 'For Alex Ross, Honorary Jewish Wagnerite.'"

I include this anecdote repeated from my "Pandemic Wagnerology" not to be self-serving or disingenuous but as cautionary. While it may seem a reasonable response from an ardent Wagnerite like Ross to someone who considers himself an apostate in a process of detoxification from Wagner and Wagnerism like me, the status quo of non-Jewish Wagnerites remaining the custodians of Jewish sensibility and opinion about Wagner, even when they appear to be in happy partnership with us, should be more open to input. As with the Wagner Societies, once it's judged that one's Wagnerism credentials are inauthentic or otherwise lacking, the predictable result is ostracism.

Wagnerism discourse as we've known it should have no more right to being an exclusionary club than orchestras should continue to have an easy pass on excluding women or other arts institutions to relegate people of color. While Jews rank among its members, the Wagner Society of New York, the site of Ross's Wagnerism launch and where Vaget recently did an engaging presentation on the Jewish context of Der Fliegende Holländer, has kept its distance from the likes of Gottfried Wagner, Marc Weiner and me.

When Leonard Bernstein welcomed the Black Panthers into his living room, the scoffing of skeptics was unanimous. A repeat of such a moment is something you're not likely to find anytime soon in the living rooms of WSNY. Nor, alas, can we look to Ross and his book for a more probing inquiry into the origins, history and place of Wagner Societies in Wagner appreciation and promotion.

There's a psychology and strategy at work in Wagnerism. By being honest about the seriousness of Wagner's antisemitism and at the same time placing Jews and antisemitism in much broader, diluting contexts of complexity, other constituencies and concerns, the intention and hope is conveyed, albeit tacitly, that the monster will be thereby defanged. Now that we know this devil, we're safer and on more sure footing than when he was the devil we didn't know or admit to knowing as such.

It would be as if in our telling the truth about their racist hegemonics while appreciating them in broader contexts of regional and historical narratives, the confederate statues that have dominated central locations in Southern and other American cities can be left in their current places with qualifying plaques and the resulting expectation that their toxicity will be thereby defused.

Likewise with Nazi sculptor Arno Breker's bust of Wagner, which glowers like a security guard in greeting visitors to Bayreuth. It seems implicit that if we add plaques, extra program notes and mount occasional exhibits, we can continue to indulge with impunity the cultism that venerated a romanticized Southern world made possible by slavery, and the antisemitic art that so incomparably influenced and continues to dominate musical culture and that enabled the greatest recorded atrocity of genocide in the history of civilization.

Arno Breker, leading artist of the Nazis, created three Richard Wagner busts which continue to welcome visitors to Bayreuth. Other Breker Wagner family busts in Bayreuth's Festival Park and environs include those of fiercely antisemitic Cosima Wagner and Hitler confidante and collaborator Winifred Wagner. Breker is also known for his busts of Hitler, Goering, Goebbels and Speer.

Though Ross does refer to the "soulless statues in the style of Arno Breker," of statues of Wagner in America he notes that the best known of these, in Baltimore and Cleveland, "still stand, despite occasional calls for them to be removed." When it comes to the tests of time, at least for the foreseeable future, Wagnerism too will likely stand its ground.

Ross's principal motivation seems to be to do whatever is necessary, including getting even more serious about the most difficult truth, not only to chronicle but to honor and preserve Wagnerism, the biggest obstacle to which in our time continues to be the ongoing fallout from Hitler and Nazism. The alternative — a quantum depedestalization of Wagner with its possible outcome of a relegation of Wagner in the repertory— remains unthinkable to Ross and fellow Wagnerites.

In this Parsifalian quest to make things right and with impressive sleight of hand, Ross manages to shift the onus for the association between Wagnerism and Nazism onto Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a leading racist and antisemitic theorist who married into the Wagner family. While it's plausible that Wagner himself might have had real problems with Hitler and Nazism, and Ross is always measured and qualified even in supposition, it does seem wishful thinking and less than fully persuasive to thus exculpate Wagner. Chamberlain did not write Parsifal.

Ross is determined that Wagner himself, however appropriately scolded or judged, will not be held primarily and certainly not enduringly or surpassingly responsible for Hitler and Nazism, however impressive ever-gathering circumstantial evidence might seem. And even if Wagner should be thus indicted, that can't be expected to supersede something as all-encompassing and all-important as Wagner appreciation. It can't be expected to unseat something as mighty, as vastly inspiring, as life-giving and enhancing, as sustained and sustaining as the opiate of Wagnerism.

It's like indicting religion, "the opiate of the masses," or the Church for the Inquisition and genocides of millions of indigenous peoples in the Americas. Whatever the criticism, however serious, however true, religion and the Church will prevail, however dogged and shadowed by politics and history. And likewise Wagnerism, in the future trajectory of which Alex Ross's testimonial will be a cornerstone.

Like the Wanderer standing against Siegfried, Wagnerites have what seems infallible authority. While the Confederate statues in contention with Black Lives Matter include figures of renown and daring, there is no equivalent among them, not remotely, of the sovereign genius of Richard Wagner, of what Thomas Mann called "the greatest talent in the entire history of art." Surely, such a superman must prove exempt from the rules of engagement for mortals.

Like no other work on Wagner or musical culture, Wagnerism makes the case for Wagnerism's legacy of influence on art and as well on stirrings and movements of minority and sectarian consciousness. Inevitably, as Wagner himself can seem to have foretold, his artwork of the future would wander from its path of being revolutionary and invincible to losing its footing along the shadowy byways of the future that became history. As the Buddhism that kept beckoning to Wagner doubtless helped him foresee, nothing of this world is forever.

Epilogue. A close friend, Joel— a gay, liberal fellow Georgian whose grandfather fought in the Confederacy — and I were discussing the fate of Confederate statues. What should be done? Our first thought was that they should be consigned to arts parks, like those where statues of Marx, Lenin, Stalin and other Communist figureheads have been left to weather and leer at one another in former Soviet bloc countries. Alternatively, how can we mitigate the toxicity of these taxpayer funded (to the tune nationally of $40 million) relics of slavery and emblems of racism without getting into the unsavory business of interfering with artistic freedom? Joel's suggestion was that rather than remove them, we should consider placing statues of American Civil Rights leaders in meaningful juxtaposition to them. Opposite that of Robert E. Lee, for example, consider placing a statue of Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, John Lewis or Barak Obama.

Meanwhile, there's a new statue, the first in 60 years for Central Park in New York City. The Women's Rights Pioneer Monument, as it's called, honors Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They are the first women to be so honored, to break the "bronze ceiling" of what was heretofore a club for men only in Central Park, as most everywhere else.

In Germany today there are no legal public statues of Nazi figureheads. The issue of related figures, like Wagner, appears to have thus far skirted major protest. In my exchanges with Marc Weiner about the Breker busts, it's clear that neither of us has the heart or stomach to be involved in anti-art initiatives, notwithstanding the deep empathy we share for Black Lives Matter and other activism around minority concerns, including those of Holocaust survivors.

Meanwhile, I recall a postcard from Germany during WW2 that showed Hitler in apposition to Einstein. Putting aside tough questions of the public subsidization of such vestiges of Nazism as the Breker works, in a hypothetical future reconfiguring of public art for Bayreuth, which historical figures might occupy appositional places for Wagner?

In his penultimate chapter, "Siegfried's Death,"about the Nazi period and the war years, Ross notes that in recent seasons Breker's Wagner bust at Bayreuth has been "hemmed in" by an exhibit called "Silenced Voices" — a series of panels of Jewish musicians who served at Bayreuth into the Nazi period and perished during the war, a number of them at death camps like Theresienstadt. Were any sent to Flossenburg in the environs of Bayreuth, where Wieland Wagner was appointed titular head by Hitler and where 30,000 inmates were murdered?

Possibilities for figures that could give dimension and context to Wagner do come to mind: Giacomo Meyerbeer, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Hermann Levi, Friedelind Wagner, Arturo Toscanini, Lauritz Melchior, Friederich Schorr, Lotte Lehmann, Bruno Walter, to name a few.

And Gottfried Wagner? Farfetched as it might seem to pose such a comparison, are Gottfried, the most outspoken Wagner family member on the issue of his family's complicity in Nazism, and his aunt Friedelind Wagner, the only outspokenly anti-Nazi Wagner family member who risked her life and legacy to leave Germany during the war, less worthy of being rendered in bronze in the environs of Bayreuth than Winifred Wagner?

Though Winifred is known to have helped some Jewish artists escape persecution, Ross notes that her record of loyalty to Hitler and the Festival was "unwavering." Have we been tacitly granting surpassing credit to never-repentant Nazi collaborator Winifred Wagner for maintaining and guiding the festival through the period of her intimate friendship with and enthusiastic support for Hitler and Nazism, and beyond from the sidelines via the leadership of the Festival she designated for her sons, likewise never explicitly publicly repentant Nazi collaborators Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner?

In his chapter, "Venusberg: Feminist and Gay Wagner," Ross observes that "moral crusades in art seldom succeed in felling their targets, and Wagner is no exception." A corollary is that just as the BLM-led felling of Confederate statues cannot rewrite the legacy of racism and slavery, appositioning Breker's busts and statues with others cannot reconfigure the legacy of antisemitism and the Holocaust.

However daunting the prospects and challenges of change, a process of reconfiguration, if not yet the particulars, would begin to take shape as we become willing to step forward, in transition from the ancien regime of Wagnerism. In the shadow of Black Lives Matter and other movements of minority and sectarian consciousness and activism — including those seeking greater accountability for, and some of them inspired by, Wagnerism — the future will chart its own course.