Art, Addiction, Enfants Terribles and Monstres Sacrés

“Heroin, be the death of me Heroin, it’s my wife and it’s my life… ” – Lou Reed, “Heroin”

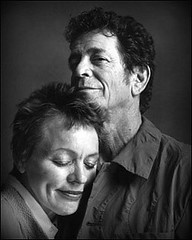

Figure 1 - “Queers in Love! Bi guy Lou Reed marries lesbionic performance artist Laurie Anderson today” by feastoffun.com, Creative Commons

“Not pleasure alone lies close to my heart. In the midst of joy I crave after pain.” – from Tannhäuser’s Ode to Venus

Figure 2 - Grace Bumbry as “Black Venus,” Bayreuth, 1961, bibliolore, The RILM blog

In his song, “Heroin,” Lou Reed admits surrendering to his addiction to opiates. In a film biography, “Born To Be Blue,” musician Chet Baker chooses heroin over his family. In Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni, *the antihero is unapologetically addicted to seducing women. In Wagner’s *Tannhäuser, by contrast, the protagonist seeks to escape his enslavement to erotic pleasure.

All addicts need healing, what we call recovery. But not all addicts want it and fewer still want it badly enough to pursue it and stick with it, even when it’s a matter of life and death, as it inevitably tends to be. After years of fighting drugs and alcohol, Reed and Baker joined the multitudes of their confreres who died while still actively addicted to alcohol and drugs. Don Giovanni remains evermore defiant as his sex addiction accelerates. He dies unrepentant, as he is carted off to hell. Among these exemplars of addiction, despite several near-relapses, only Tannhäuser sustains his commitment to healing. All achieve posthumous redemption, Wagner’s great theme, via art.

Wagner wasn’t known to be alcoholic, drug addicted or sexually compulsive, but like Tannhäuser, he struggled with character defects and troubled inclinations that cast a dark shadow on his life and work. Tannhäuser dies in his quest for the grace he finally achieves, but Wagner’s fate is more like Moses’s. Wagner’s descendants—his music dramas—are granted entry, albeit increasingly qualified and monitored, into the promised land of enduring artistic acclaim while the composer himself is detained at the pearly gates.

Figure 3 - Alison Bechdel at the Boston Book Festival by Chase Elliott Clark, 10/14/11, Wikimedia Commons

For his 75th Birthday I took my life partner Arnie Kantrowitz to see the musical Fun Home, based on Allison Bechdel’s memoir of growing up lesbian with a closeted gay, alcoholic father. “Fun Home” is short for the funeral home where Bechdel’s father worked and which serves as a metaphor for the moribund state of their family relationships.

I found myself keyed into the mystery that is at the play’s center: why couldn’t she and her father find a way to better communicate, be more real and genuine with each other, and be friends? That almost happened on some occasions, but inevitably the father would retreat into the closet and isolation, into drinking and otherwise effortful imitations of being the dad, breadwinner and standard-bearer. Allison, meanwhile, longed to understand her father’s private life, feelings, beliefs and hopes, so many of which she was sure they shared. But it was never to be. What she was left with were fragments of memory, a few posthumous revelations, and lots of questions and unresolved feelings.

In Fun Home, the protagonist goes back in time to her first glimmerings of awareness of her father’s gayness, his compulsive trysts with young hustlers, and his drinking. The extent of her father’s drinking is more implicit than clarified in the play. Like his daughter, Mr. Bechdel is creative, with an interest in literature and theater.

Like Bechdel’s father, and more than my other immediate family members, my brother Steve Mass always seemed to be not present, off in another world, preoccupied, evasive, and hiding secrets. On so many fronts it seemed we were kindred spirits. Even with his being 6 years older than me, why couldn’t we bridge the communications gulf between us?

My field is addiction medicine and I myself am a person in recovery. Not surprisingly, I am primed to see people through this lens. Not unlike homosexuals and many artists throughout history, addicts are perforce alienated from society, which so unrelentingly misunderstands, stigmatizes, neglects, abuses and discourages them when they are most vulnerable and struggling. Yet they are admired and rewarded with outsized adulation when successful. How society treats addicts and artists is not unlike how the Romans treated gladiators. We aversively condition them, like dogs for dogfights, to kill and die for us. When they succeed, we venerate them as champions. Top gladiators have been described as the rock stars of their day. When they are less than champions, we abandon them, often contemptuously.

In the age of Trump, the public stigma upon and neglect of opiate addiction has turned evermore deadly. There simply is no other way to describe the tens of thousands of deaths of the opioid crisis that have been preventable but which the public, with its ignorance, prejudice and especially its politics, still widely abets. Beyond fitful, patchwork progress, it still recoils from understanding, compassion and life-saving actions such as needle exchanges, opiate maintenance, detox, rehab, overdose prevention and other treatment services. A more serious and sustained approach with genuine leadership would also help prevent attendant epidemic recurrences of HIV and Hep C infection such as those that rocked Mike Pence’s Indiana. Alas, the promises of preventive medicine have no more currency than environmental protections for an administration hellbent on deregulation and cost-cutting at the expense of science, common sense and humanity.

It’s difficult to overstate the problem of stigma addicts the world over still face. The death squads of Philippines dictator Rodrigo Duterte’s death war on drugs seems of a piece with the empty rhetoric and gestures of the Trump administration. As social outsiders and often enough literally outlaws, however, addicts do tend to share traits that are not always wrongly regarded as antisocial or sociopathic, especially when they choose to reject treatment and recovery, as they so often do.

Stereotypically, addicts not yet stabilized in treatment and recovery are characteristically in situations of emergency. They are invariably absent or late for events, in some kind of trouble, often legal and financial, and defensive with excuses that don’t add up. The cumulative impression you have with an active addict is that a real person simply isn’t there. They’re not dependable or reliable. Honest communication and genuine intimacy are always elusive. They’re disingenuous and emotionally unavailable, except when a scarcely concealed need for money or refuge emerges from a guise of caring. This is why most of the significant others of addicts who aren’t in recovery eventually fall by the wayside after years of codependence, enabling, and mollification. Though it’s predictable that an addict will take family members and significant others hostage emotionally and financially, it’s likewise characteristic for even the most codependent of enablers to eventually see the light and want out.

Psychoanalytic theory, which Freud and his followers developed and which dominated American psychiatric practice for decades, is now mostly history. Though psychoanalysts are still in practice and psychoanalytic constructs and methods are still respected and utilized, their older explanations for human behaviors have long since given way to behavioral and biological models.

Two examples of the death knell of older psychoanalytic theory are homosexuality and drug addiction. As psychoanalysts struggled to retain their theories of homosexuality as a developmental disorder of family relationships (e.g., the overbearing-mother-and-absent-father paradigm to explain male homosexuality), sexology was running rings around them with new studies (Kinsey, Masters and Johnson, Bell and Weinberg) that were far better-researched, far less obviously biased and far more sophisticated in perspective. In less than a generation, psychoanalytic explanations of homosexuality became completely discredited. This does not mean, however, that psychoanalysis no longer had anything of interest or value to say about homosexuality or to gay people.

The same is true of psychoanalytic theories of drug addiction. Today, if you are diagnosed as an alcoholic or drug addict, no mainstream physician or institution would send you to a psychoanalyst for initial or primary treatment. Rather, you would most likely be guided into various levels of addiction treatment—detoxification, rehabilitation and long-term recovery using 12-step programs based on the model of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Early psychoanalytic writings did, on the other hand, hit the nail on the head in their characterizations of the behaviors of drug addicts. These turn out to be the same behaviors psychoanalysts have observed in artists and gay people—behaviors that fall under the rubric of what they call “narcissism.”

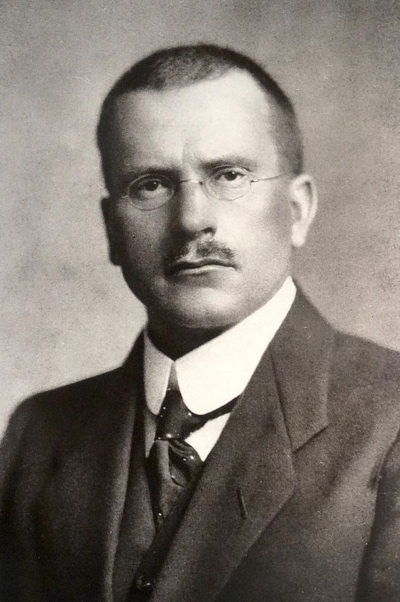

Figure 4 - Carl Jung, Wikimedia Commons

Narcissism is a key psychoanalytic concept that is used primarily to describe the psychopathology of self-absorption and concomitant retardation of emotional development. Simply put, narcissism can be understood to mean immaturity. In common parlance, narcissists are people who feel entitled the way children do and who lack a developed sense of responsibility in interpersonal relations. Because narcissism can also be described as an absence of empathy or spirituality, it’s not surprising that the addiction recovery movement was indirectly spearheaded by Freud’s more spirituality-oriented acolyte, Carl Jung, and further developed by Dr. Harry Tiebout, another psychiatrist of that period of the mid-1930’s who envisioned spiritual development as key to behavioral change.

Figure 5 - Dr. Harry Tiebout, Alcoholics Anonymous, aa.org

The recovery landmarks that emerged—the “Big Book”of Alcoholics Anonymous and 12 Steps and 12 Traditions—are remarkably consistent in expressing that addiction was, as manifest in attitude and behavior, a disorder of emotional and spiritual retardation and impairment. As these founders of the recovery movement noted in their literature (from 12 Steps and 12 Traditions): “We...had to admit that we were childish, emotionally sensitive and grandiose.”

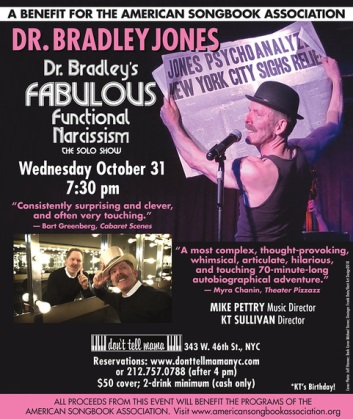

A fascinating window on all this is provided by Bradley Jones, an openly gay psychoanalyst in New York who came to his profession via his publicly acknowledged experience with drug addiction (primarily cocaine). For Jones, the “God” and “Higher Power” concepts of recovery, developed from the Christian-identified principles of the Oxford Group, proved troubling. Though 12-Step recovery is explicit about not being allied with any denomination or sect but does conceptualize “God” to be “as we understood Him,” Jones was more drawn to the paradigms of psychoanalysis. He sensed that the serious underlying psychodynamic issues in his interpersonal relations were less about “Higher Power” and “spirituality” than what Jones himself identifies as narcissism.

His journey took him not only from recovery to psychoanalysis but to actually becoming a psychoanalyst. As conveyed in his indeed fabulous one-man cabaret show, “Dr. Bradley’s FABULOUS, Functional Narcissism,” his self-realization took place primarily via “self-psychology,” an offshoot of psychoanalysis developed by Heinz Kohut.

In his show, Jones, who was a member of the cast of A Chorus Line on Broadway, dances and sings his journey with perception, elan, and passion. For someone with such talents, and as the show reveals, it was challenging to learn how to relegate the self to become more right-sized, to becoming, as 12-step recovery puts it, “a person among persons.” But how inspiring to see a person take what recovery can seem to relegate as a character defect, narcissism, and turn it into a principal engine of creativity, self-realization and celebration.

Figure 6 - “Dr. Bradley’s Fabulous Functional Narcissism,” starring Dr. Bradley Jones, theatrical poster

While it may seem that artists and addicts are the way they are because they are wounded from their upbringing, or because of the self-preoccupation that can seem bound up with their creativity, their behavior is often perceived as narcissistically troubled. Like addicts, many artists feel that they must have what they must have when they must have it, regardless of consequences. If an addict or artist must break the law to meet his or her needs, so be it. If she or he must dominate, exploit, endanger, neglect or abuse to meet needs, so be it.

When otherwise unremarkable adults behave this way in everyday life, they may be regarded as sociopathic. When they happen also to be admired artists, we call them enfants terribles, after the 1929 novel Les Enfants Terribles, by Jean Cocteau. If they are of even greater stature, say a Picasso or Wagner, we may call them monstres sacrés, after the 1940 play Les Monstres Sacrés, also by Cocteau, himself a heroin addict.

Les Enfants Terribles is about a twisted sibling relationship literally poisoned with opium addiction. For an artist and/or addict to be an enfant terrible or monstre sacré is like having an exemption, a free pass from the harsher expectations and judgments of society. As Donald Trump put it in terms of his fanatical base, “I could shoot somebody and not lose any voters.” The same might be said of another great category of celebrities—artists. Figuratively, and sometimes literally, if their base is strong enough, they can get away with murder.

Figure 7 - Jean Cocteau, author of Les Enfants Terribles and Les Monstres Sacrés, Studio Harcourt, 1937, Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Among the exemplars of this aspect of artists is Picasso, who famously observed that when he was a fledgling artist he was taught to paint like an old man, but when he became an old man, he finally learned how to paint like a child. It’s an insight about creativity that everyone can appreciate. But the flip side of this indulgence of the inner child, the price of being childlike in circumstances requiring maturity, tends to be glossed over or ignored.

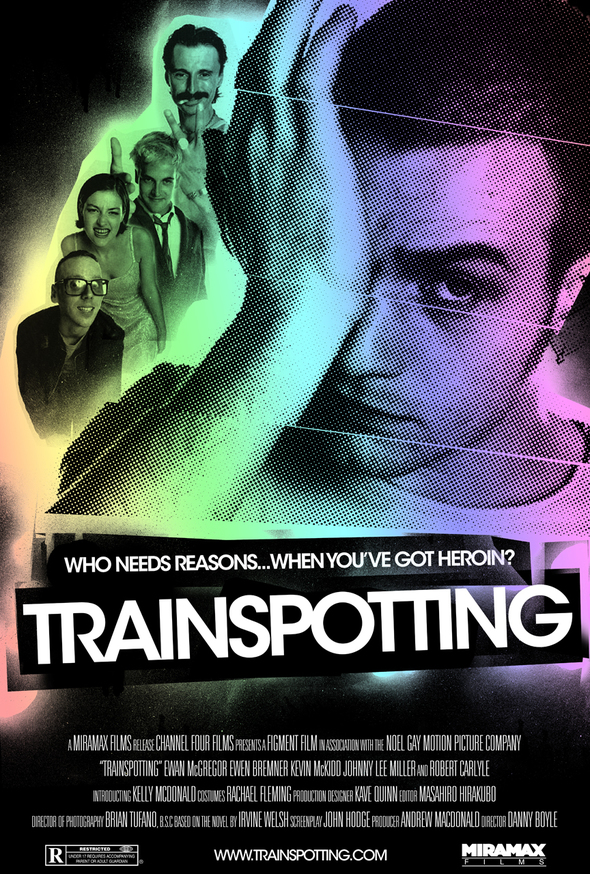

The disconnection from reality and responsibility addicts seek is captured in many images and stories. Tannhäuser is a good one, but none is more trenchant than a key scene in Danny Boyle’s film, Trainspotting, about heroin addicts and their lives. The camera begins a startlingly slow-motion scan of heavy drug usage, mostly of heroin, in a crash pad, capturing a panorama of addicts in advanced stages of intoxication. Eventually it settles on an unwitting participant, the baby of one of the addicts, now dead from hours of neglect. In the greater perspective of addiction so incomparably achieved by Boyle in Trainspotting and Trainspotting 2, as in the constructs of state-of-the-art addiction medicine, craving and seeking are seen to trump everyone and everything else.

Figure 8 - Trainspotting, directed by Danny Boyle, Miramx, 1996, theatrical release poster

Because of Jackson Pollock’s stature as a great artist, and notwithstanding his vehicular manslaughter of a girl (and injury of a second passenger, his mistress) during a drunk-driving spree, the wreckage of his personal life and its alcoholic deaths are couched in a certain romance. The same is true of writer William S. Burroughs, a gay man and opiate addict who “accidentally” killed his wife in a drunken William-Tell-like game. Her death was declared “culpable homicide.”

Gaugin is another of these easy-pass monstres sacrés, an artist whose decision to abandon his wife and children to pursue his art became legendary—culturally sanctioned, admired and envied. The list of “bad boy” artists is not simply big. It’s more the rule than the exception. This is how important art is to the artist, artists believe and their admirers accede, whatever the consequences.

Figure 9 - artanddebt.org

Acceptance of Wagner can be seen in this context as a manifestation of our exoneration of ugly and reprehensible behaviors and prejudices—arrogance, theft, adultery, bullying, exploitation and malignant antisemitism—in the name of art. And however we may judge his work, Wagner’s most infamous and ardent disciple, Hitler, was also an artist. Even Donald Trump’s pathological narcissism seemed initially blunted by being sold as the “art” of the deal.

License to be a narcissist is a given in the world of artists and celebrities, just as it is with addicts. Gay people, so neglected and abused by the intractably arrogant, ignorant and vicious, were outraged when society expected us to change as well. Even though it was true that too many of our behaviors were self-destructive and endangering to public health, such as high-risk sex and drug use as the AIDS epidemic raged. Gay people, who share backgrounds of neglect and abuse with artists and addicts, likewise share with artists and addicts great reservoirs of anger at the otherwise overbearing indifference, expectations and regulations of mainstream society. We’ve tended to hold society responsible for all our troubles and to regard it with a retaliatory, reciprocal contempt.

This drama of the individual versus society has been striking as well during the Covid-19 pandemic, but in this case, the resistance was primarily with religious and other far-right political extremists who balked at social distancing and mask guidelines, especially when they became mandates. Just as the unsafe sex many gay men balked at giving up in the wake of bathhouse and other sex venue closures posed a health hazard to society, so did religious and political gatherings pose risks to society amidst the pandemic of Covid-19. Hence the title of medical ethicist Ron Bayer’s book, Private Acts, Social Consequences.

Artists, addicts, queers, transgender folk, punks; creative people, outsiders, and social misfits with issues and grievances. This is the world Steve Mass fit right into. He understood the psychology of artists, of those who feel misunderstood, struggling to find their place and have their say. He was one of them, though he wasn’t gay, wasn’t a more stereotypical social misfit and had no real artistic talent. He was not a visual artist or musician. Nor was he a writer, though at various points he flirted with the idea of becoming one.

Nor did he appear to have any great love of specific artists, musicians or writers. At home or otherwise with us, his biological family, Steve was not someone who went around singing the praises of music that had seduced him. Nor did he reflect worshipfully on great artists or wax ecstatic about books he had read by favored writers. He was never seduced by any specific writer, artist or musician the way I was with Wagner.

Rather, Steve’s creative gift turned out to be something related but different—being entrepreneurial. In this, although he never sustained their levels of success, he can be compared to other cultural entrepreneurs—e.g., Leo Castelli, Henry Geldzahler; oh, and Wagner’s agent, Angelo Neumann.

Though he dabbled in philosophy and cultural studies and commentary, Steve’s skills were more in the area of identifying, nurturing, staging and marketing creative individuals, subcultures and energies. Easily at home with art and artists, Steve seemed more inspired by the business of art than by art per se.

Early on, he demonstrated a sophisticated appreciation of the art market. In casual conversation he’d talk more about the Rockefellers, the lives of the super rich and corporate CEO’s, than about specific artists, writers and musicians. On the one hand, icons of financial and corporate success were the people we were all in rebellion against. On the other, with their material trappings of success, of wealth and power, they were the ones everyone had fantasies of being. When the Mudd Club became big, Steve took flight lessons. Like CEO’s who experience sudden jackpot success, perhaps he’d soon have his own jet.

At Northwestern University where he studied philosophy, Steve has said he took inspiration from Melville Herskovits, founder of the university’s African Studies program and whose Myth of the Negro Past was considered groundbreaking in advancing the cause of ethnic equality. Another influence at Northwestern, prominent Germanist Erich Heller, loomed larger.

Like Steve, Heller was a lifelong bachelor and also the son of a Jewish physician. He barely escaped Nazi Germany where he was imprisoned briefly by the Gestapo for his anti-Nazi writings. In recalling her uncles, Erich and his brother Paul (who endured much worse persecution by the Nazis), Caroline Heller wondered if Erich’s escape might have been paid for with sexual favors.

When Steve was at Northwestern majoring in philosophy, Heller came to our home in Chicago to influence our parents to support Steve’s taking leave of his studies to travel abroad. I’ve no certainty that Heller was gay and notwithstanding all the gay life in his orbit at the Mudd Club, I never had any sense that Steve was. Perhaps Heller was gay and hoped that something would emerge with Steve. And who knows, maybe something did happen at whatever level. It happened like that between Wagner and King Ludwig, where Ludwig’s homosexual inclinations were subtly played upon by Wagner. Or perhaps Heller hoped Steve, as a Holocaust survivor (even if Steve never consciously thought of himself as such) might bring his youth, Jewish heritage and impressive intelligence to bear on the fallout of Hitler and Nazism.

Heller is said to have made only one trip back to Germany after the war, at which time he met with his old colleague Martin Heidegger, the acclaimed philosopher and Nazi collaborationist whose love affair with Hannah Arendt provides another window on the social masochism of even the best Jewish minds. Whatever reconciliation of viewpoints Heller had hoped for with Heidegger apparently did not happen.

Figure 10 - Erich Heller, National Portrait Gallery

What Steve’s place was in all this remains a mystery. Though he would bring home monographs on such giants of philosophy as Hegel, Kant, Jaspers, Kierkegard, Engels, Kafka, Schopenhauer, and Marx and must have had significant knowledge of Wagner, I never had the sense that Steve cared very much about philosophy or German culture per se, any more than he cared about any other writer or artist or anybody else per se. To my knowledge, though he lived in Germany for decades, I don’t think he speaks much German.

Rather, academic philosophy was a world where for whatever reason, personal and/or intellectual, Steve had entree and an opportunity to set out on his own path, to ease on down the road of his own life, wherever it might lead, that individual path being the kind of realization of subjective knowledge and experience, of self, that philosophers like Heller, Kierkegaard and Nietszche tried to explain and extol.

“Know thyself,” Thomas Carlyle’s great exhortation, was also the culmination of Wagner’s philosophy of self-realization, albeit within racial awareness. From Siegfried’s perception of the genetic otherness of his foster-parent, Mime, an intensely antisemitic caricature, to Parsifal, where the pure fool learns to recognize his calling through intuitive compassion for his own kind (his fellow whites and Germans), the individual’s journey of self-actualization was thematic in Wagner.

Beyond some journal fragments, what Steve brought back from his travels abroad were several Dutch-masterly paintings, portraits and still-lifes that ended up on our family’s walls. One hangs in my living room. My sense is that with these purchases, even if he had little sense of it at that time, Steve had begun his career, his calling, as a middleman of art, fashion, and culture.

Figure 11 - Unidentified portrait by unidentified artist, one of the first pieces of art collected by Steve Mass, photograph by Lawrence D. Mass

Even in his post-graduate stint with the University of Iowa Creative Writing Workshop Steve seemed to distinguish himself more as an entrepreneur than as a writer, dropping out of the program before completing it. I don’t recall any real writing Steve ever did, there or elsewhere, before or since. Apart from the journal fragments he kept during his travels, mostly during the Mudd Club years, there was no writing anyone ever heard about and nothing he wrote was published or even rumored. If you google Steve Mass, there’s nothing written by him.

During that stint in Iowa, however, Steve began his own publishing company, producing works of some artists of renown, like a collection by the poet Maryann Moore. Alas, the quality of the publishing was rudimentary. There were a lot of printing and editing errors and Steve quickly found himself beset with complaints and financial problems. Though his immersion in this milieu of creative writers and writing doubtless informed the highly original happenings of the Mudd Club, to my knowledge Steve never returned to writing or publishing. Now in his early 80’s, he hopes to write a memoir of the Mudd Club, his own version of a history already written and published by Mudd Club doorman Richard Boch.

Couching the bursting creativity of the Mudd Club were other initiatives—a medical concierge and ambulance service, a stint in teaching ESL (English as a Second Language) at Touro College, collecting Haitian street art, and a restaurant in Soho. What they all had in common were two characteristics that would plague Steve and those in his circles throughout his life: financial crisis and what might be called vacancy of personhood—that is, a sense that there was no real, identifiable person behind the entrepreneurial facades.

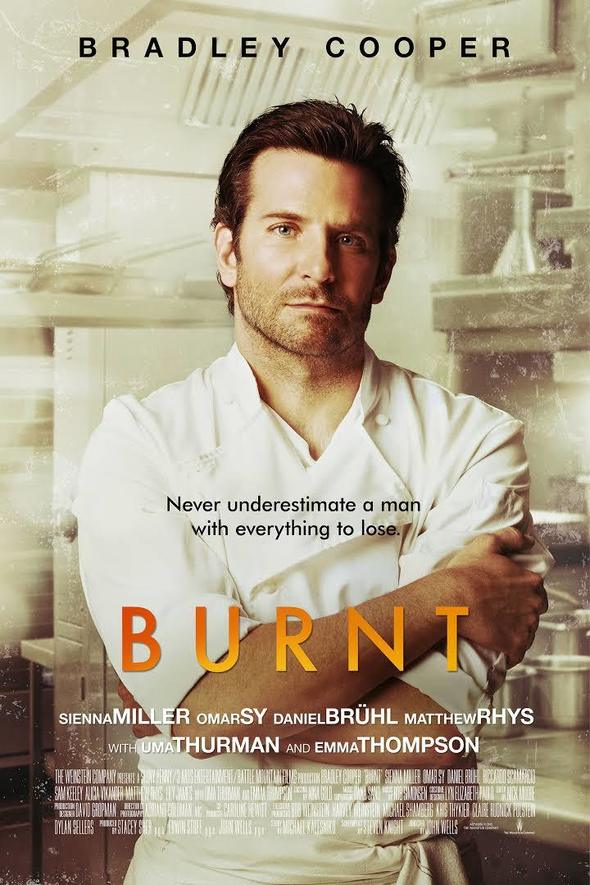

Figure 12 - Burnt, directed by Steven Knight, The Weinstein Company, 2015, theatrical release poster

There’s a film that came and went with little notice. It got mostly bad reviews, mostly deserved. It was called Burnt and starred Bradley Cooper. It’s the story of an exceptionally gifted celebrity chef and drug addict who managed to destroy every opportunity he’d ever had and alienate all those who tried to love and help him.

In addiction recovery, people talk about “the wreckage of the past.” Here, the wreckage was gross and everywhere. What happens in the film is that the Cooper character, still beloved and believed in by leading restaurateurs and ex-lovers, managers and foodies, finally agrees to enter recovery. Miraculously, his old love sees him through and with her inherited money is able to settle his considerable debts. A happy ending.

For much of his life, Steve, like the Bradley Cooper character and also like Wagner, was plagued by debt. He seemed always in financial crisis, as artists and drug addicts are wont to be, even those with outsized fame and success—e.g., Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, Judy Garland, Jackson Pollock and so many others. Just as typically, arrogance and attitude betrayed insecurity. This similarity of the traits and circumstances and hurdles of his own life to those of addicts and artists seemed the basis of a genuine empathy on Steve’s part. The hand-to-mouth, for-the-moment way of life, the willingness always to pay the price of crisis—of recklessness and irresponsibility—for their individuality, for meeting their needs, for being themselves, for their creativity— is the way Steve lived. Art and addiction. This was his milieu. Artists and addicts. These were his people.

Inevitably, however, there were those realities of business and finance. Like the culinary efforts of the Cooper character in Burnt, Steve’s Soho restaurant, Bernard and Steve’s, tanked under the weight of expenses and the exigencies of operations. Of course, in the intersecting worlds of art and addiction, those seeking payment of debts were cast as outsiders—squares, villains and buffoons.

Those who became patrons of famous artists were sometimes gratefully enshrined as such—e.g., Wagner’s patron King Ludwig, Tchaikovsky’s Madame von Meck, and people like Theo van Gogh, Peggy Guggenheim and Marylou Whitney. Just as often, however, patrons are also seen by artists, especially those who are struggling, as chumps. This mentality is well-captured in the film Basquiat, directed by Julian Schnabel and featuring David Bowie as Andy Warhol. One scene takes place in the Mudd Club (re-created for the film), where Basquiat was able to feel at home as a painter, musician and heroin addict. Another briefly features Steve Mass himself, nonspeaking and grimacing with lust for the bar lady, a snapshot that seemed to convey little of the reality of Steve’s actual personal life.

It may be that my sense of Steve as one whose sex life was relegated to creative life is a distortion from being a family member. It’s difficult to be real, to be sexual, to laugh without restraint, to really have fun, to be uninhibitedly creative, to be truly and comfortably yourself and alive with your own family. For childish but also for practical reasons you don’t want them to know the real you. For family, you become this pretend person of exaggerated family expectations—of caring and responsibility, of personal sacrifice, of morality and ethics, of duty, of loyalty, but consequently also of reticence and disaffection. That pretend person is not someone anyone wants to be, but rather feels pressured to be.

Virtually every coming-of-age story is about breaking with one’s family—for addicts, artists, gay people and most others. And it’s as sobering for me to realize that I was part of that family system for Steve as he was for me. Steve did not want to be the desultory older brother of the sibling who entered a profession, earned a regular pay check, and succeeded financially and professionally on a sustained basis. Nor did he want to have to endure the endless codependence struggles that are embedded in virtually all family relationships. For Steve, with whom brotherhood was sometimes like living in a play by Eugene O’Neill, I was a participant in that drama. Like O’Neill, the master of family drama and its dynamics, and the many other writers who chronicle failed family relations, however, we were better at calling out, indicting, judging and leaving our families of origin than genuinely transcending them.

There was one big moment of exception to the recurrent financial crises with Steve: when the Mudd club hit its mark of being the premiere downtown new-wave alternative to the uptown citadel of old-guard glitz that was Studio 54. In the heart of an after-hours no man’s land that otherwise had the appearance of a ghost town after the workday of nearby Wall Street, the club quickly became this huge success, and money was pouring in. Eventually, even Studio 54 icons Steve Rubell, Halston and Trump’s mentor Roy Cohn showed up there.

Figure 13 - Roy Cohn with Joseph McCarthy, UPI, 1954, Wikipedia Commons, public domain

I don’t recall Steve ever mentioning to me either of his principal collaborators and co-founders, new-wave art curator Diego Cortez and downtown punk scene figure Anya Phillips, but he did pay respectful tribute to Phillips in the most substantial interview with Steve from those years (East Village Eye, 11/83, by Leonard Abrams). Whatever the challenges of management—stealing by bartenders was a continuous problem—such was the club’s success that Steve was able to buy the building that housed it at 77 White Street. Alas, a year or so later, dire financial trouble reemerged when Steve was investigated for alleged attempted bribery involving an IRS officer. It was a debacle from which neither the Mudd Club nor Steve’s finances would recover. Steve lost the building that was subsequently bought by its earlier owner, artist Ross Bleckner. The club closed soon thereafter.

Apart from the financial trouble, the club had run its course after several years. Like many restaurants and plays, clubs tend to be short-lived. Downtown began to emerge from its deep sleep of decades, an awakening the Mudd Club had iconically inspired. Accompanying that awakening was the epidemic that would soon become known as AIDS, decimating the gay men, trans folk, artists and drug addicts that dominated the club’s ranks.

Steve never suffered any other enduring legal sanction we knew of, but again he was broke or seemed to be. In Burnt the Bradley Cooper character is menaced by goons, loan shark types; at one point, he’s beaten up. We never learned anything very specific about Steve’s financial troubles. In the wake of the Mudd Club’s demise, Steve was involved in new enterprises—the medical and ambulance business followed by the restaurant, both of which were short-lived, despite flickerings of possibility. A fellow physician and friend who worked for Steve had no complaints, and the food at Bernard and Steve’s, when you finally got it, was distinctive and deserving of its good Zagat rating. A restaurant postcard captured the moment with a hulking Bernard in a white wedding dress, looking skeptical and disgruntled, as he clasped hands with Steve, the happy groom, clutching a bouquet of flowers.

The collapse of these enterprises in the wake of the demise of the Mudd Club in 1984 set the stage for Steve’s relocation to Berlin, where artists could expect more support from the socialist government and where bohemia seemed once again ascendant; fertile ground for new shots at life, and club life.